Talking commons, enclosure and the possibility of a re-commoned economy on RNZ

Plus the Regulatory Standards Bill as ‘enclosure on steroids’

This week I chatted with Mark Leishman on RNZ Afternoons about my new book ‘An Uncommon Land’. We covered a lot of ground, from the mundane (how did the peasant farmers grazing their pigs in the commons know which pig was theirs?) to the profound (the erasure of commons through enclosure and the ascendancy of private property, and how this shapes society today).

Another question Mark asked me, I suspect unwittingly, was the connection between the Regulatory Standards Bill and the commons. (My answer in short was that it is the antithesis of commons.)

And it occurred to me on reflection that the release of my book, in the same month that the Regulatory Standards Bill was introduced, was timely in a deeply ironic way.

The Regulatory Standards Bill progresses the libertarian view that those with property rights (corporations, business and land owners being obvious examples), should be able to exercise those rights unencumbered by any but the most necessary regulation (eg, regulation to maintain national security, or some minimum level of public safety – but probably not public health because in the purist libertarian view, what people choose to consume or expose themselves to is their own decision).

We know that in our neoliberal economic system, polluters or those who damage the environment through their activities rarely pay for the damage (what economists call externalities). Instead these are ‘socialised’: society and the environment absorbs the cost, for example through public health impacts of pollution, a dangerously heating climate, collapsing fisheries and pollinating species, and so on. In other words, beyond the enclosures of physical commons in pre-industrial times, neoliberalism has further enclosed our commons. It has allowed land, oceans, freshwater and air to be polluted and extracted for private sector gain, and to enhance property rights (the value of land and other assets, and share values).

But the Regulatory Standards Bill goes even further. It requires us ‘commoners’ to pay (not metaphorically, but literally in money) for any ‘impairment’ of property rights resulting from regulation requiring polluters to stop polluting, damaging or extracting from our commons.1 This is enclosure on steroids.

It is important that we are alert to the fact that enclosure, which began with the fencing off and reclaiming of the common lands so it could be converted to property for private gain, is still being progressed. But in ways that are less obvious yet more pervasive that the enclosure of a field, or the draining of a fen. Owing to the calculated efforts of wealthy and powerful corporate and political forces, our national and global commons continue to be enclosed (irreversibly damaged or destroyed).

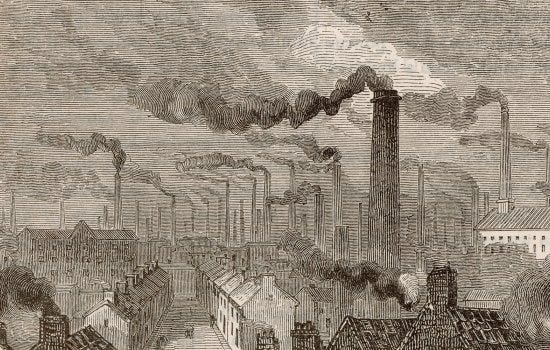

But on top of this, as people, we have also been enclosed. From commoners, and then citizens, we have become (primarily) consumers. We have become robotic cogs in a global money machine that extracts from the planet at rates far beyond sustainable, to produce goods that do not enhance human wellbeing (or in many cases, actively harm it - think cars, junk food, social media, alcohol, plastic consumable products, pesticides) for the sole purpose of enriching wealthy individuals and corporations. This is a continuation of the process that began with the dispossession of peasant farmers from their lands through enclosure, destroying their ability to support themselves without selling their labour in the smoke-blackened industrialising cities.

As I set out to show in ‘An Uncommon Land’, we do not have to go so far back in our own ancestries to find at time that it was normal for people to grow their own food, make and mend their own clothes, fix or repurpose broken furniture or machines, exchange surplus, cooperate on common good initiatives, and socialise with one another through conversation, music, dance and games.

Not everything about our past was good – we need to leave a lot of it behind. But there is an important distinction between societal progress (eg, advancement of human rights, values around equity) and change that has been imposed upon us by an economic system (capitalism), specifically designed to enrich a small minority at the expense of the rest of society.

It is critical that we understand that the process of enclosure continues today, including through our own government’s regressive legislative agenda. We need to be alert to these efforts and not only resist them, but insist of something different. That is, an economic system with human wellbeing not perpetual growth as its primary purpose.

Listen to the interview on RNZ Afternoons here.

Read my submission on the Regulatory Standards Bill here.

Note that so-called ‘regulatory takings’ is also a feature of proposals to replace the current Resource Management Act.