I first published this post in 2010 on my environmental history blog envirohistorynz. With the current government’s preoccupation with growth at all costs and a renewed focus on mining, I thought it might be salutatory to reflect on the incalculable environmental (and fiscal) costs of past mining operations in New Zealand. It would be interesting to find out how much the remediation of the Tui Mine cost the New Zealand taxpayer in the end. If anyone knows, please share in the comments.

A tale of mining in New Zealand – and the tragic tailings of Tui Mine

In the increasingly impassioned debate about mining (for example the estimated 50,000-strong march in Auckland on 1 May), it is helpful to have an understanding of the history of mining in New Zealand and the implications it has had. As with many other environmental issues, there are important lessons that can be learnt from our history.

A general history

Interest in our country’s mineral resources dates back to the 1840s, when European settlers began searching for gold and other metals, and coal. Gold was discovered in Otago, the South Island West Coast and the Coromandel, leading to gold rushes in the 1860s. The surface deposits of gold were soon exhausted however, and larger scale mining developed in the 1870s to extract the less accessible deposits.

Mining of gold and other minerals soon burgeoned, and by the time Geological Survey director, James Hector, reported on the the minerals and mining industry in New Zealand in 1870, gold, silver, copper, lead and iron had all been discovered, and small-scale mining was under way. All the main goldfields and coalfields had been established, and coal was being mined in many areas around the country. Production of gold varied, but peaked about 1905 and then gradually declined. In contrast, coal production grew steadily to 1 million tonnes in 1900, doubling to 2 million tonnes in 1910, and stayed around that level for the next 70 years. The total value of mining output (excluding oil and gas) increased steadily after the Second World War, and exceeded $1 billion for the first time in 2004. The increase was due to changes in mining technology and in the products produced, and to increases in export markets.

Tui Mine – the story of a “modern-day” mine

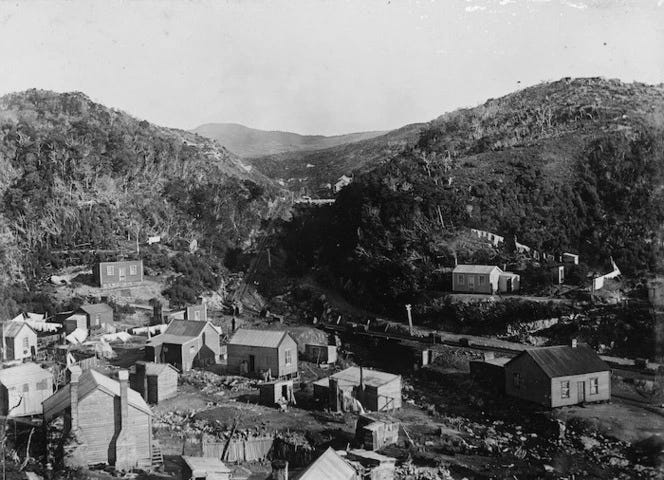

The Tui Mine is located on the western slopes of Mount Te Aroha in Waikato. Mining at Tui Mine began in the 1880s but stopped about the turn of the century. It didn’t resume until 1967, under a consortium called Norpac Mining Ltd, comprising a New Zealand company, an American company and a Canadian company. The mine extracted various metals including copper, lead and zinc. However, after a number of years of prosperity, from 1973, overseas buyers would no longer accept the minerals, owing to unacceptable levels of mercury. The mine became uneconomic, and in 1975, Norpac went into liquidation and abandoned the mine.

But also abandoned was a large pile of ore and sand-sized crushed ore (known as “tailings”) containing significant amounts of zinc and cadmium, which was dammed to prevent it slipping down the mountainside. Left unmaintained, this has become increasingly unstable over the years, leaching minerals, including heavy metals, into the Tui and Tunakohoia streams. These streams are now virtually “dead” – i.e., contain no fish-life whatsoever and almost no invertebrates, owing to their highly contaminated state [see Environment Waikato report for more details]. While some maintenance work was done in 1980 by the Hauraki Catchment Board, the dam has continued to destabilise. Alarmingly, there remains a real risk that the dam will collapse, inundating the Te Aroha township below [click here to view location] with an estimated 100,000 cubic metres of contaminated waste.

In 2007 the government announced that nearly $10 million would be made available to clean up the site, with the work scheduled to be completed by 2010. However, in April 2010, the Dominion Post reported that the estimated cost of the clean-up had been revised to $17.4 million. Meanwhile, the hapless Te Aroha township continues to be threatened by potential calamity.

The mine is now considered to be one of the most contaminated sites in New Zealand.

While the profits from the mine during its operation went directly to the owners of the mine company, the ongoing cost of its remediation – whether $10, $20 or $30 million – will be borne by the taxpayer. On the other hand, the cost of its failure to be remediated continues to be borne by the surrounding environment, and, potentially, even more disastrous consequences by the residents of Te Aroha township.

Sources/further reading: Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Contrafed Publishing, The Dominion Post, Ministry for the Environment, Environment Waikato.

Thanks for the historical perspective. Something we see all to little of in current analysis of 'Fast Track' mining. The long term consequences of these sorts of initiatives are simply dismissed or played down. Short term profit - perhaps - but as this example demonstrates , the long term costs will have to be picked up by our grandchildren.

😱Appalling all around up to & including today 😡